Milshtein was six at the outbreak of the Second World War and eleven as it drew to a close. Those formative years saw him swept along on a veritable Odyssey: hand in hand with his mother and older brother, they escaped their native Bessarabia ahead of the advancing Nazi armies. During two years, they fled back and forth across the vast area between the Aral and the Black Sea seeking refuge before finding it in Tbilisi, Georgia, during the winter of 1943. Their flight into the USSR followed the 1939 Soviet appropriation of the Romanian province of Moldavia and Milshtein’s father’s subsequent deportation to Siberia. By setting out, in search of the husband and father that they were never to see again, the little family was spared the tragic fate at the hands of Nazis that so many others would not be.

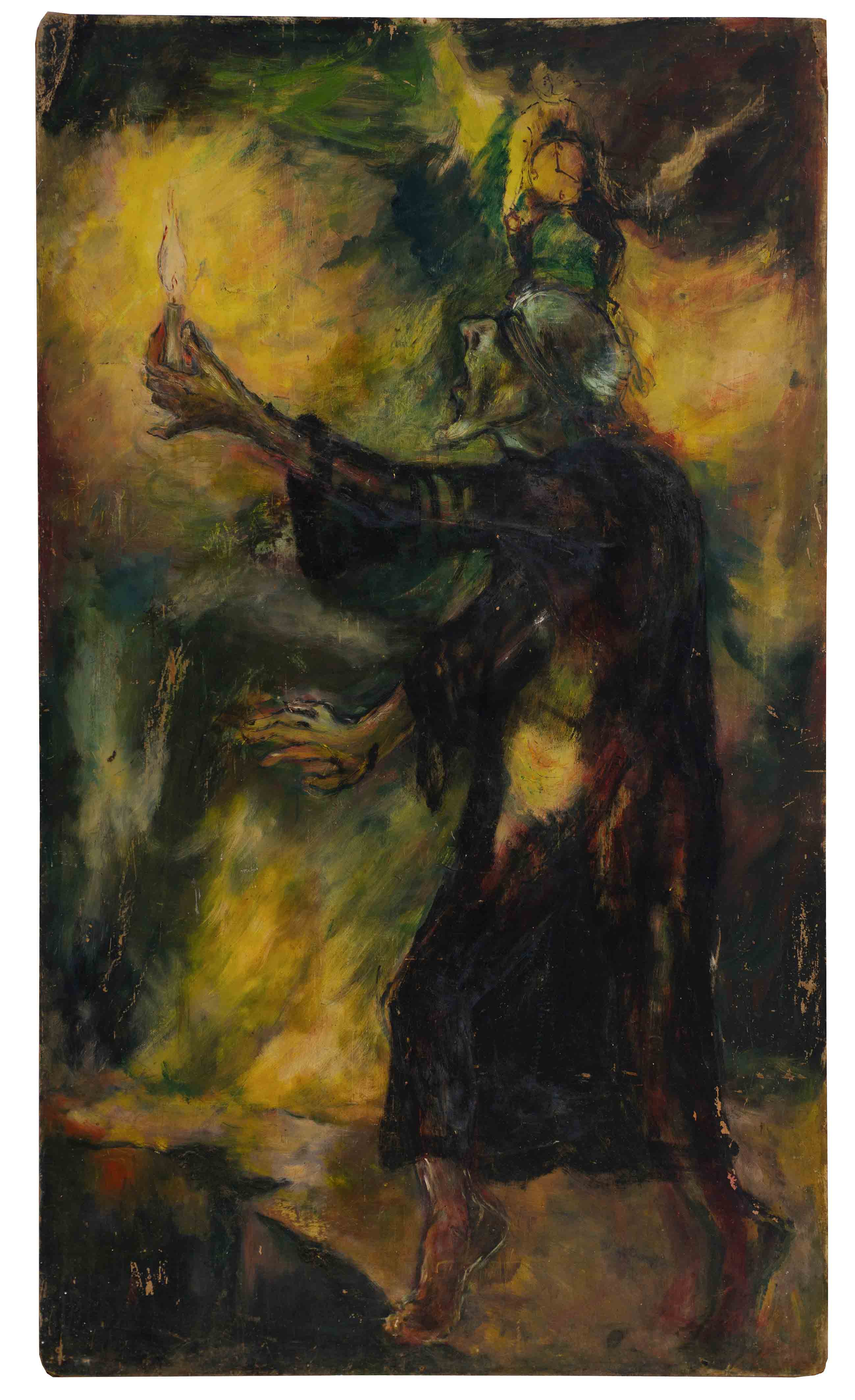

This period of exodus, stamped by dark visions of bombings, of famine and the deaths of fourteen million Russians, is at the core of Milshtein’s inspiration. It binds him to a nocturnal universe cross-hatched by images of railroad tracks, stabled locomotives, of rare treats of fried eggs, and of vodka drunk amongst the muzhiks they encountered on their way. These images, at once starkly illuminated by the glare of tragedy but suffused by the glow of humanity, were nourished during his adolescence in Israel by the stories their mother recounted, in answer to their questions on their years of wandering and of the strange circumstances which she, a woman not yet turned thirty, experienced in order to keep them alive. The images of their endless, almost burlesque, journey are superimposed on a backdrop of an inky darkness in which hover the countless specters of all those never to be seen again.

This exile, this mourning for a world redeemed by maternal love, is the keystone of Milshtein’s oeuvre. Trained at the outset of the Modern Art movement by teachers from the Bauhaus, first in Georgia, then Romania, Cyprus, Israel and finally in Paris, where he furthered his career from 1956, Milshtein evolved his unique vision, playing on the glow of naked, female flesh set against all that pierces the shadow cast by its brightness, rather than revisiting the horrors drawn deep from the well of his memories.

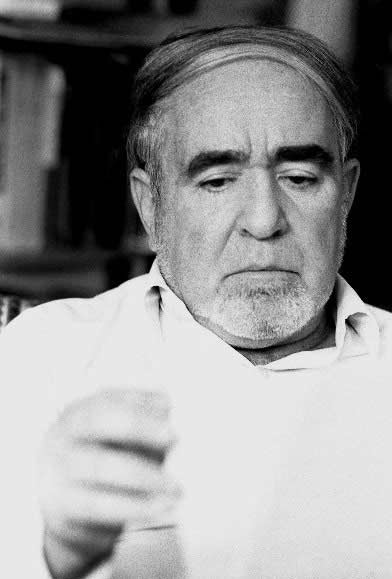

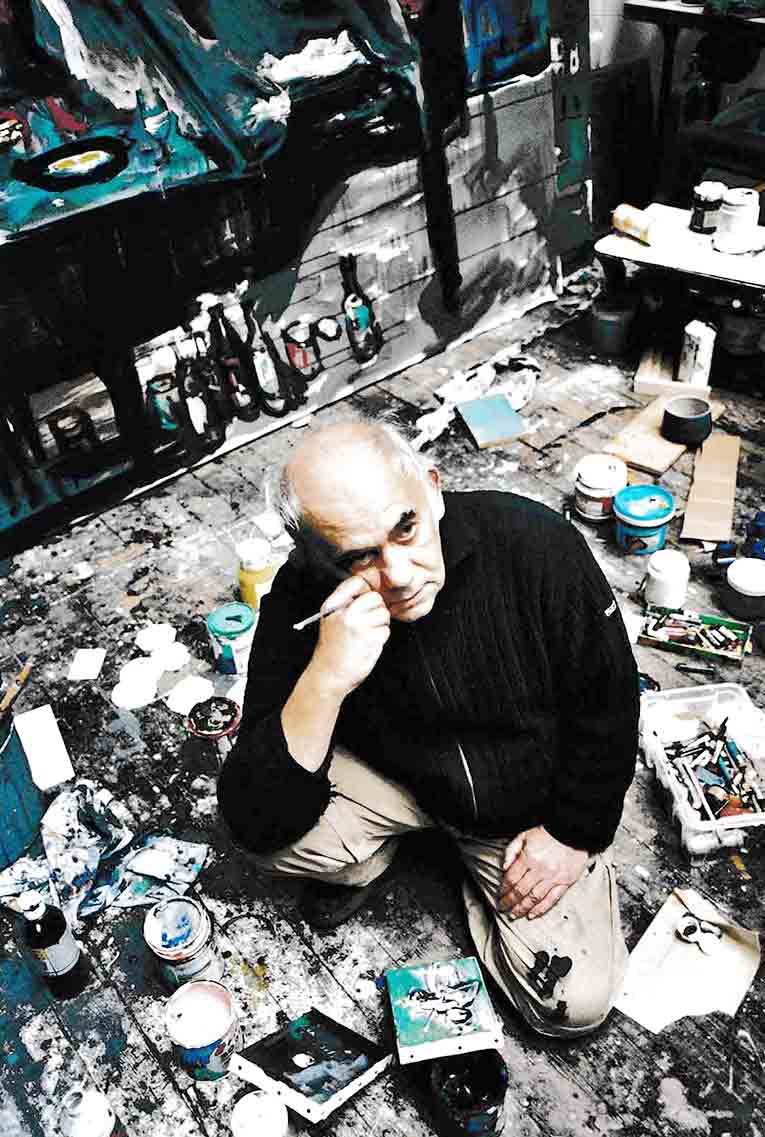

Painter, engraver, sculptor, writer, paper-maker, book-maker, chess-player, lover of Love and of vodka, Milshtein thrived in the half century after the war as a protean artist, enamored by color, as by the written word and the twinkle in a beautiful eye. He currently continues his acclaimed career, as attested by an uninterrupted string of exhibitions in art museums and galleries on all four continents.

Robert Albouker 2017

1934

Grigory Isakevitch Milshtein, aka Grisha, born 25 June 1934 in Kishinev (Moldova), then a province of Romania, to Riva Rosenfeld and Isaac Milshtein four years after the birth of his older brother, David.

His family belong to the town’s moneyed, Jewish bourgeoisie. His father is a prosperous businessman, head of a cooperative bank, working for the Jewish-American organization, “The Joint” (Jewish Joint Distribution Committee) of which he is the regional director for Romania.

1935-38

The Milshteins live in a pretty villa on Reninskaya, near Pushkinskaya.

“The walls of my room, all covered in depictions of fairy tales, left a deep impression on my imagination. All the walls of the house were painted, there wasn’t a square centimeter that wasn’t”.

GGrisha and his brother are tutored by a Swiss governess, Madame Martin, who teaches them French from a very young age.

1939

Soviet forces enter Moldavia as a result of the pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviets.Isaac Milshtein is arrested and deported to Siberia, convicted for having relations with a foreign power.The Milshtein’s home is seized.

1940

As the family of a deportee, the Milshteins are forced to live outside the provincial capital of Kishinev.

1941

The German-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact breaks down on 21 June 1941 when the Nazis launch an offensive on Soviet territory. Argueiev, Kishinev, Kiev and other towns are bombed.

Autumn 1941. David, Grisha’s older brother, persuades their mother to flee to the Soviet Union if she has any hope to see her husband again.

“My mother sold the last of her jewelry. We left by train. It was an exodus. People were fleeing everywhere ahead of the advancing German army. The roads were full of ox-drawn carts and long columns of refugees. Time was suspended, dream-like. People travelled on vehicle roofs, holding on to doors… we all wanted to get as far away as possible. We thought to ourselves that the Nazis would never get as far as Asia and we wanted to get to Siberia and find my father. We were escaping…”

Despite the bombings, at the end of 1941, the Milshteins reach Krasnodar, Russia, where they have an elderly relative…

They find refuge on a kolkhoz.

“We would stop in kolkhozes where my mother could do a bit of work and find what to feed us with. I remember a rag factory, where my mother worked sorting what could be used. For a day’s work she was paid with a bun… at that time, the greatest culinary delicacy we had was fried eggs”.

Milshtein is 7 years old. Badly afflected by privation, he falls dangerously ill and has to be hospitalized for several months.

“In Krasnodar I was in hospital for two or three months… in the street, my mother bumped into the man who had been our family doctor in Kishinev and who had become a captain and medic in the Red Army. He saved my life, as he still had a small supply of medicines in reserve”.

1942

Fleeing the continued advance of the Nazis, the Milshteins leave Krasnodar in the Northern Caucasus’ area of Southern Russia.

1943

The Milshteins continue their flight from the Nazis, endeavoring to reach Makhatchkala, on the Black Sea, in order to get to Georgia by boat and contact a cousin of Riva Milshtein’s. This cousin is the wife of Akaki Mgeladze – Stalin’s cousin – and president of the Soviet Republic of Abkhazia, adjoining Georgia. They eventually reach the mountainous passes of the Caucasus, referred to as the military route, leading to Georgia. Once in Tbilisi, the Georgian capital, Riva Milshtein’s cousin puts a home she owns at their disposal. Milshtein is admitted to the Pioneers’ Palace in Tbilisi. He attends drawing and painting classes and manifests an early fascination for the ambience of the artist’s atelier.

“The walls of the studio were hung with copies of famous paintings, of naturalist landscapes that were a very literary translation of the ambience in the world of painting at the start of the 20th century. I remember one day seeing copies being made of official portraits of Lenin and Stalin, inch by inch. My inability to deal with the abstract may come from that period of my life, where I was taught that there is no art for art’s sake, rather that art is for the masses…”

1944

Age 10, Milshtein studies drawing and painting.

“At the studio, the students painted on what they found. We had no supplies: paper was something very precious and almost unobtainable. Newspapers were very rare. Just to buy one, and only one, required waiting in long lines. At school, we were obliged to use the space between the lines of used notebooks to write as well as in the margins. Greco-Roman busts were set on display as models to practice drawing, and bizarrely, a bust of Rosa Luxemburg was amongst them”.

1945

Summer of 1945 and the war is over. To reach Kishinev and return home, the Milshteins cross from Baku to Odessa by boat and meet up with the cousin who had come to their rescue in Georgia.

1946

Back in Kishinev, the Milshteins find themselves in unfamiliar surroundings, in a world that has forgotten them and forgotten by them. Their home is occupied, their family, their friends, their neighbors, uncles, aunts, cousins –all had perished in the war, for the most part in Nazi extermination camps. Riva Milshtein takes her family to Bucharest where she hopes she will receive help from the United States Consulate, as the widow of an employee of an American organization. The family spends almost a year there without succeeding to obtain a visa. Milshtein studies with George Stefanescu –painter and renown art historian, author of several works on icons and the history of Moldavian art who initiates him into the art of classical oil painting. Milshtein also tries his hand at lino and wood cuts.Finally, Riva Milshtein takes the decision to go to Palestine.

“Still lives done under Stefanescu started my career as a painter”.

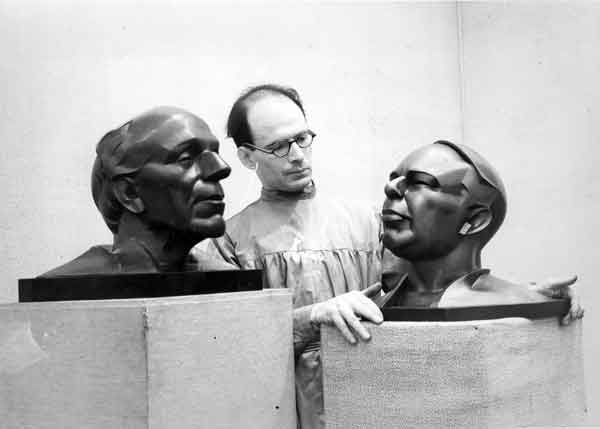

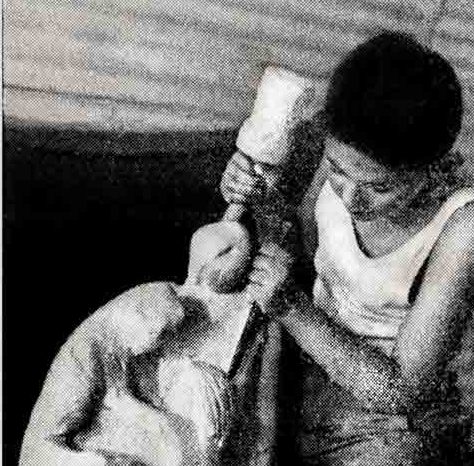

1947

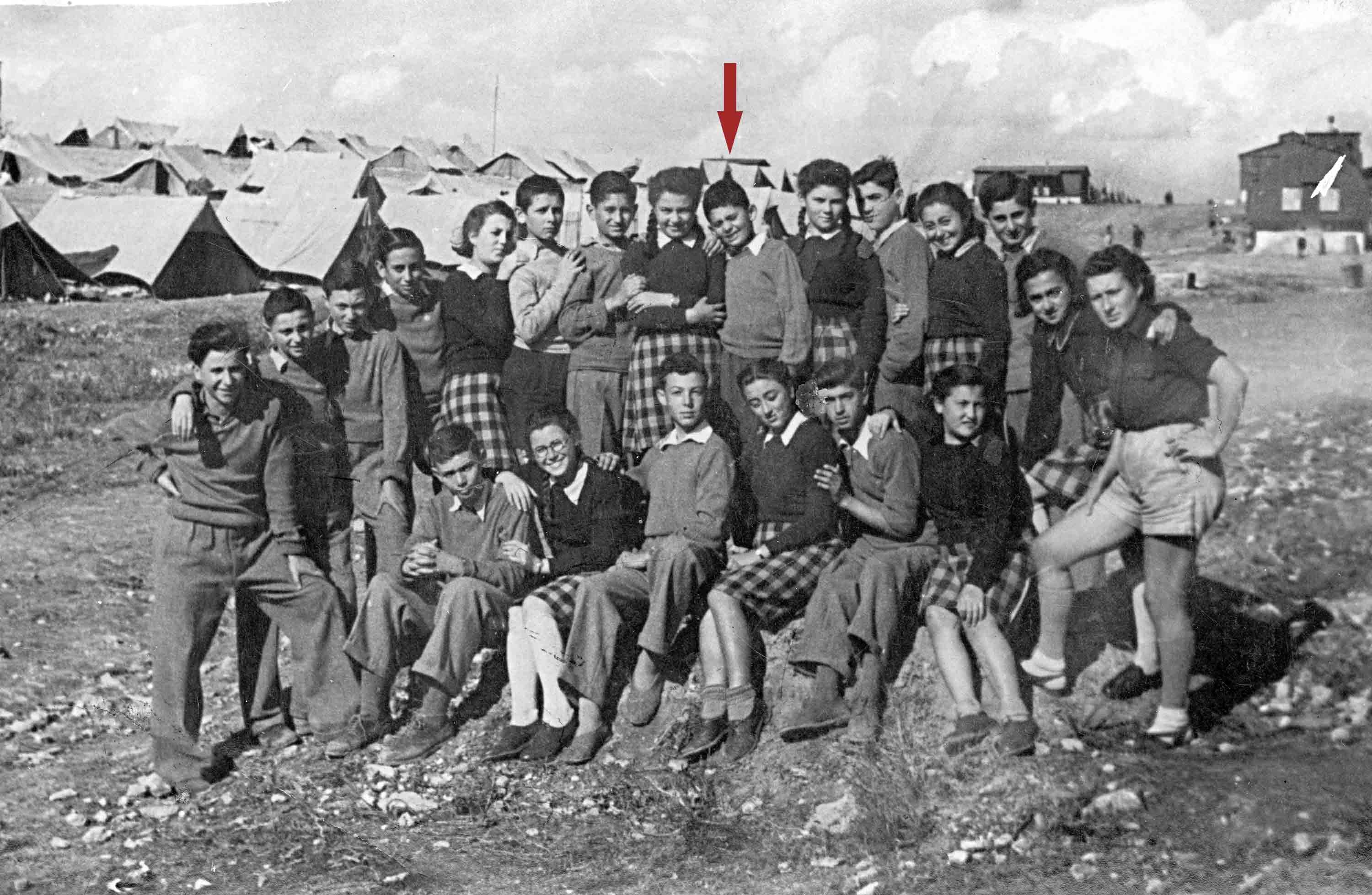

The British blockade of Palestine, to stop Jewish immigration, forces the refugee ships to Cyprus. To prevent repatriation, the organizers of the Zionist emigration obligate the destruction of identity documents. It is at this point in time that Milshtein gives up the first name of Grisha for that of Zwy. The Milshteins spend almost a whole year in the camps in Cyprus until the declaration of the State of Israel in May 1948. During that time, Milshtein resumes his art studies under the sculptor Zev Ben-Svi, sent by the authorities of the future state to take charge of the education in the Arts of the emigrants or, more likely, to keep them busy… Milshtein has a clear recollection of this period: for the first time, after so many years of rootlessness, his life becomes orderly. He achieves a certain celebrity amongst his peers when he creates a model of the ship that brought them to Cyprus. His photograph appears in a newspaper, showing him with hammer and chisel in hand. He recalls with pleasure having learnt to sculpt on the island’s stone.

Ben-Svi avait créé une « école » où je tapais la pierre. Lui faisait des œuvres en tôle martelée néo-cubistes. Certaines sont au British Museum. Le travail de la pierre provient d’éclats. On doit savoir comment taper, où donner un coup de burin, c’est une école de décision… Il m’a dit : « une sculpture taillée dans la pierre doit être compacte. Sinon, tu risques de casser un bras ». J’avais dix ans. .

1948

Arrival in Tel Aviv of the Milshtein family in the summer, a few weeks after the declaration of independence of the State of Israel. During the first year, Milshtein studies in the atelier of the painter, Madame Gita Raitler. He works on still lives in oils, a continuation of the work started under Stefanescu, in Bucharest.

1949

Milshtein, aged 15, starts to spend time in the milieu of painters and poets. The Likrat group, that formed around the poets Nathan Zach (born in Berlin in 1930) and David Avidan (1934-1995), ignites the spirit of new Hebrew poetry; its eponymous publication, to which Milshtein contributes, appears from 1952.

“In Tel Aviv, we gathered at one or another’s place, at the Café Kassit on Dizengoff Street, there were also gatherings at the Milo Club where poets and painters and intellectuals got together. We would meet up, discuss art… Amongst this group, the Habima theatre actors, who had all come from of the Vartangoff troupe, enjoyed an international reputation. They created an unforgettable staging of the Dibbuk in the 50s, with Aharon Meskin and Hannah Robina. Interesting meetings, first with poets, amongst whom Nathan Zach, stands apart at the forefront of Israeli poetry. He is a strange person, of half German, half Italian culture. You can imagine what that gave rise to. There was also Israel Pincas, David Avidan… all lovers of literature…”

He is accepted into the studio of Aharon Avni (1906-1951) who had studied at the École des Beaux-Arts in Moscow as well as at the Academy of La Grande Chaumière, before becoming one of the founding fathers of art education in the young State of Israel, where he endeavored to establish a corps of teachers, as well as mark the young artists by the openness of his spirit.

Avni a beaucoup compté pour toute notre génération de jeunes peintres, et particulièrement pour moi. C’était un pédagogue merveilleux qui a formé toute une génération d’artistes israéliens. .

1950

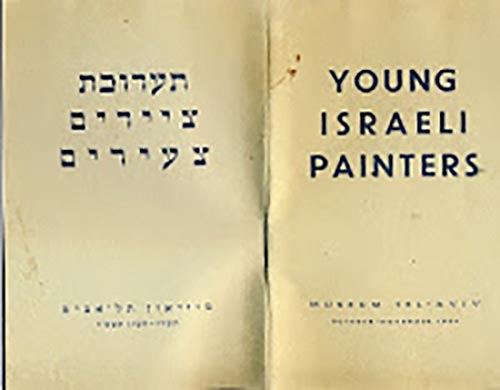

After Avni’s death, Milshtein continues his studies at the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem, as well as at the Tel Aviv School of Art. At the age of 16, he is the youngest participant in a group exhibition at the Tel Aviv Museum.

1951

Studies with Mordecai Ardon, the director of the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem, who came from the Bauhaus where he had known Kandinsky, Klee and Feininger.

1952

Milshtein studies with Moshe Mokady (1902-1975) and Marcel Yanko at the Tel Aviv School of Art, artists with whom he would meet up again later in Paris.

“At that time, in Israel, there was an incredible energy, artists believed and were more or less engaged in the Social Realism art movement… but, at the same time, doubts were starting to creep in. In Hebrew “raal” means poison: Many spoke of “Social Raalism”. There was an artistic life far removed from the pioneering spirit of the kibbutz, much closer to the artistic avant-garde of the major European capitals.”

1953

Milshtein soon started gaining a reputation.

“Altogether, there were just two or three galleries in Israel: Microstudio and the Katz Gallery where I later exhibited. Ardon and Zaritski were the painters most in fashion. Then, Mokady, Yanko, Stematski… me, I was a “rising star” and soon to have a solo exhibition at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art…”

1954

At 19, Milshtein marries Yokwed Kachi, the first woman parachutist in the Israeli Army. In the fall, he exhibits several works at the “Young Israeli Painters” exhibition at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art.

“HESITATION, which I showed at the exhibition of young Israeli painters, is a landmark work for me. It is the confirmation of my maturity as an artist and it contains all the artistic elements that formed me to that point…”

1956

Milshtein obtains a grant from the Norman Foundation that allows him to go to Paris.

“In Israeli eyes, Paris was the Mecca of contemporary art. All modern art was in Paris. In New York there was nothing, it only came later…”

Admitted to the École des Beaux-Arts, he begins with painting classes under Jean Souverbie. He abandons them quite quickly to take an etching course given by Camille. He sets himself up in a maid’s garret, at 183 Boulevard Saint-Germain. He becomes close with the sculptor Constant, and soon Joseph and Ida Constant become like adoptive parents to him. Their home, with the atmosphere of the studio and above all, of dedicated work, is an open house to young artists.

My wife and I were then living in Paris and we had just had our son, Uri. We often met the sculptor Channa Orlov. She did a portrait of my son with his mother and also bought several of my paintings that still form part of her endowment, notably YELLOW CLOWN.

Jean Fanchette, editor of the bilingual publication Two Cities, for which both Lawrence Durrell and Henry Miller wrote, became a close friend. He asked me to write for his publication and introduced me to Lawrence Durrell, who liked my work and bought one of my paintings and induced Fanchette to bring Anaïs Nin up to my garret”.

Milshtein also makes the acquaintance of Jacqueline Paulhan who introduces him to her father-in-law, Jean Paulhan.

OApart from frequenting the cafés of Montparnasse, Milshtein spends a lot of time in the Louvre. His admiration for the classics only increases.

1957

First solo exhibition in France at the Gallery Saint Placide.

Bernard de Masclary, assistant director of the Charpentier Gallery, likes his work and invites him to participate in the exhibition he is curating of the Paris School.

“I had no idea how one was supposed to behave in Paris. For example: criticizing Braque, as I did in my discussion with Paulhan, or asking whether Delacroix’s studio was for rent, were some of the gaffes I made. By the same token, I went to the Charpentier Gallery to show some of my work: Mr. Masclary liked them a lot and bought a small painting. He also proposed that I participate in the Paris School exhibition that was to take place in the following weeks. Mr. Masclary showed me great friendship and it was he who introduced me to Hans Berggruen and to many others. The Charpentier Gallery was then one of the most important in Paris. Nacenta was the owner and he argued the concept of a Paris School as being the continuation of the golden age of modern painting into our day, embracing Georges Rouault at the one end and me, the youngest, at the other”.

.

1958

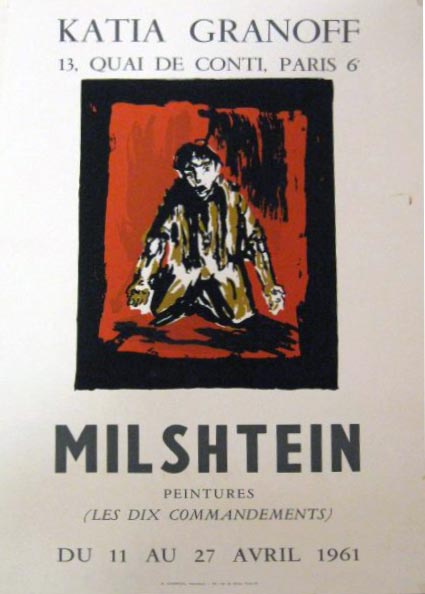

Meeting with Katia Granoff who offers him a solo exhibition.

Milshtein will remain under contract with the Katia Granoff Gallery for several years.

“The Clown Series forms a keystone work: I was in Spain and had seen the works of Goya, which led me to work on very elongated canvases that I showed Madame Granoff and that is when she decided to give me my own exhibition and put me under contract.”

1959

Eugene Kolb, director of the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, knows Milshtein’s work well and proposes a solo exhibition at the museum.

1960

Milshtein’s work starts to create a stir.

Alongside his regular shows chez Granoff, he is invited to participate in numerous other exhibitions.

1961

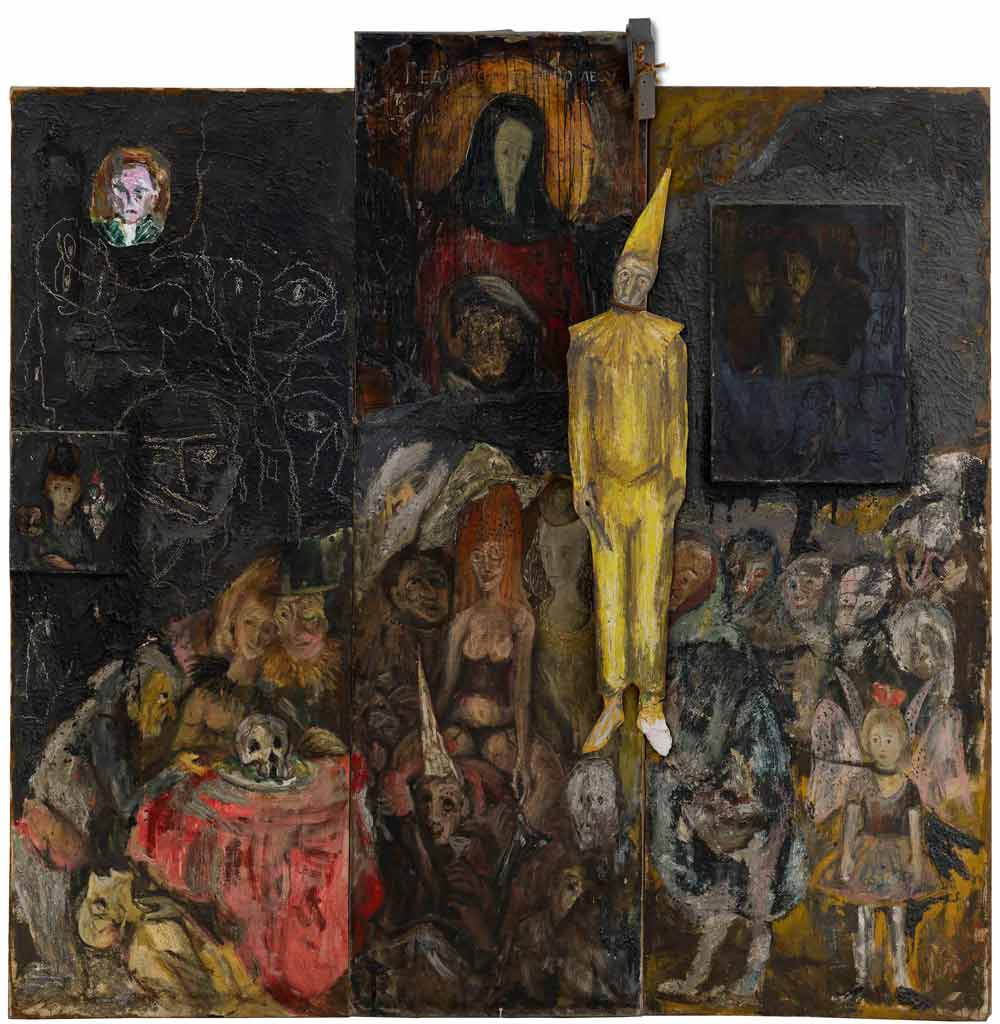

Milshtein throws himself into the creation of ambitious works, such as THE TEN COMMANDMENTS.

The renown art critic Raymond Charmet writes a review.

THE TEN COMMANDMENTS was conceived for Katia Granoff. They were works in which I used new materials. I nearly died, as the plastics I was using created an explosion. I incorporated bits on the canvas with barbed wire… They were strange, extreme collages… I believed it was a matter of universal morality that went well with my leftist leanings. It was not religious but, rather, moral…”

1962

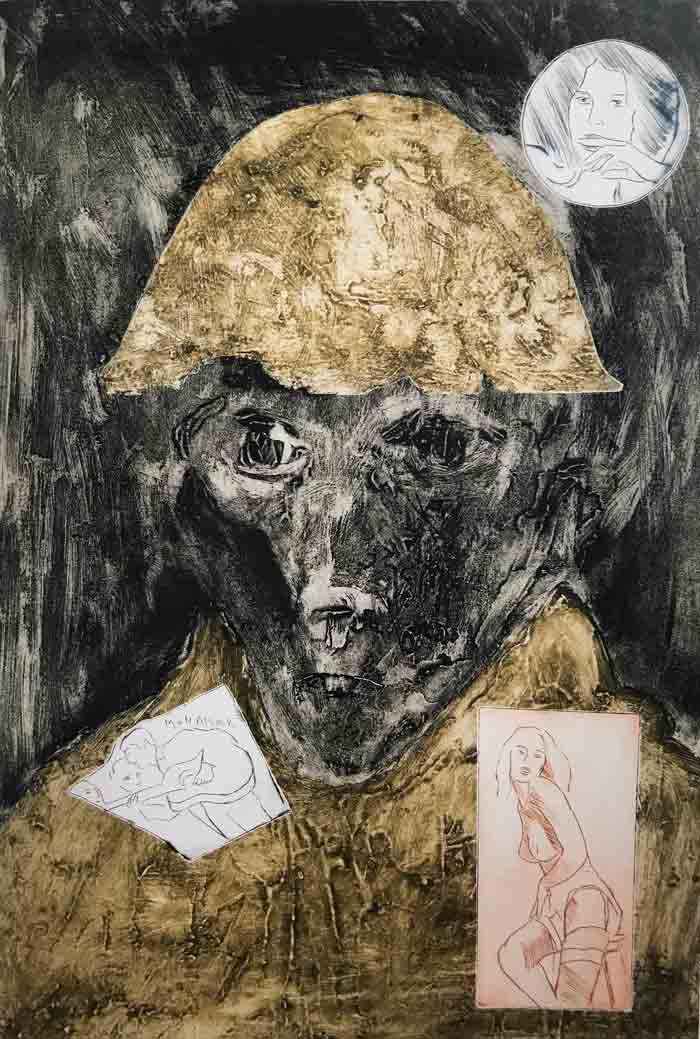

Milshtein becomes more and more passionate about printmaking and studies under Delpech.

“My passion for etching started quite early on. My first prints go back to ’46 and ’47 and were made with potato slices from which we made ‘plates’. Then there were wood and lino cuts that I did after I discovered the work of Franz Maserel, one of the few Western engravers recognized by the USSR and there was also the work of Kate Kollwitz. It was at the Bezalel Aademy in Jerusalem, that I made my first real prints. At the Beaux-Arts in Camille’s studio, I learnt a lot, particularly from Robert Nikoidski, a technician without peer, who taught me that one could be inventive and create media. In 1962 I returned to the atelier of Jean Delpech, well known for the etchings on numerous postage stamps, and attended daily: he was a great instructor”.

Premier séjour à New York, où il expose à la galerie Bodley. La ville l’impressionne fortement et pour longtemps.

Il entretient également un étroit contact avec Israël.

Il expose dans une galerie de Tel-Aviv, et également au Musée Bezalel de Jérusalem et au Musée de Bat Yam qui publie des catalogues importants.

1963

Milshtein exhibits in Switzerland, where he shows prints along with his paintings. His enthusiasm for printmaking flourishes…

“Printmaking became a great passion for me. I was printing more and more and painting less. A print is always like a trick box with secret compartments: one never knows what will come out in the print. There’s always an element of surprise. The engraving goes under the press and then you lift the paper, that’s the moment you know if it is a success or you have to start all over again. The surprise is key. Perhaps this pleasure comes from my delight in games –and my link to paper is also very important.

I adore paper and have made it myself. I find it the best base for painting. Very few contemporary painters have understood that paper is equal to a good primer. For example ICONES was done on 20 layers of primer. Paper takes paint in the same way”.

1964

At 30, Milshtein is the youngest artist with an international reputation associated with the Paris School.

1965

Milshtein meets Alexander Loewy, one of the most prestigious publishers in Paris. He publishes “MICROCOSME”, Milshtein’s first book.

“I am driven to paint, as one sees in every tiny, square centimeter of the great works of the past. That I owe to Stefansecu. My great pleasure in painting and in work was communicated to me by Avni, I have an affinity for the materials and their voluptuousness that I got from Ardon: Printmaking, painting, drawing, sculpting, all give me an equal pleasure”.

1966

Milshtein is awarded the CRITICS PRIZE for printmaking.

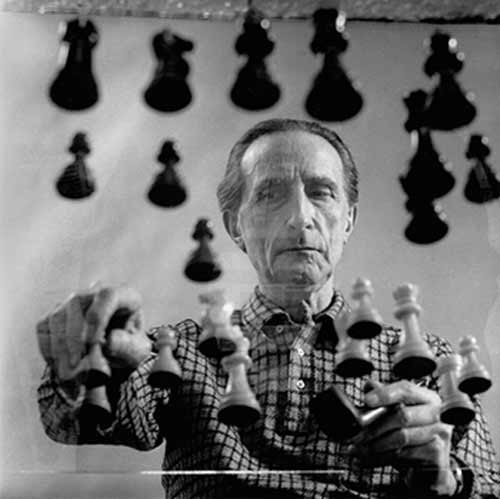

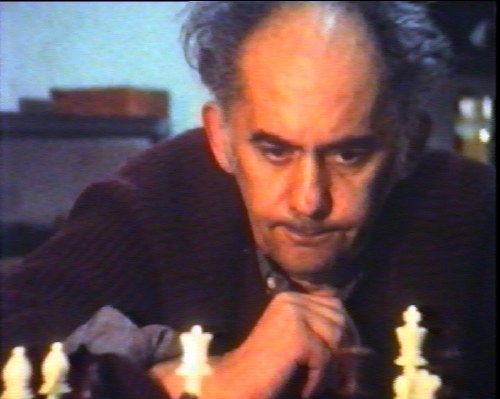

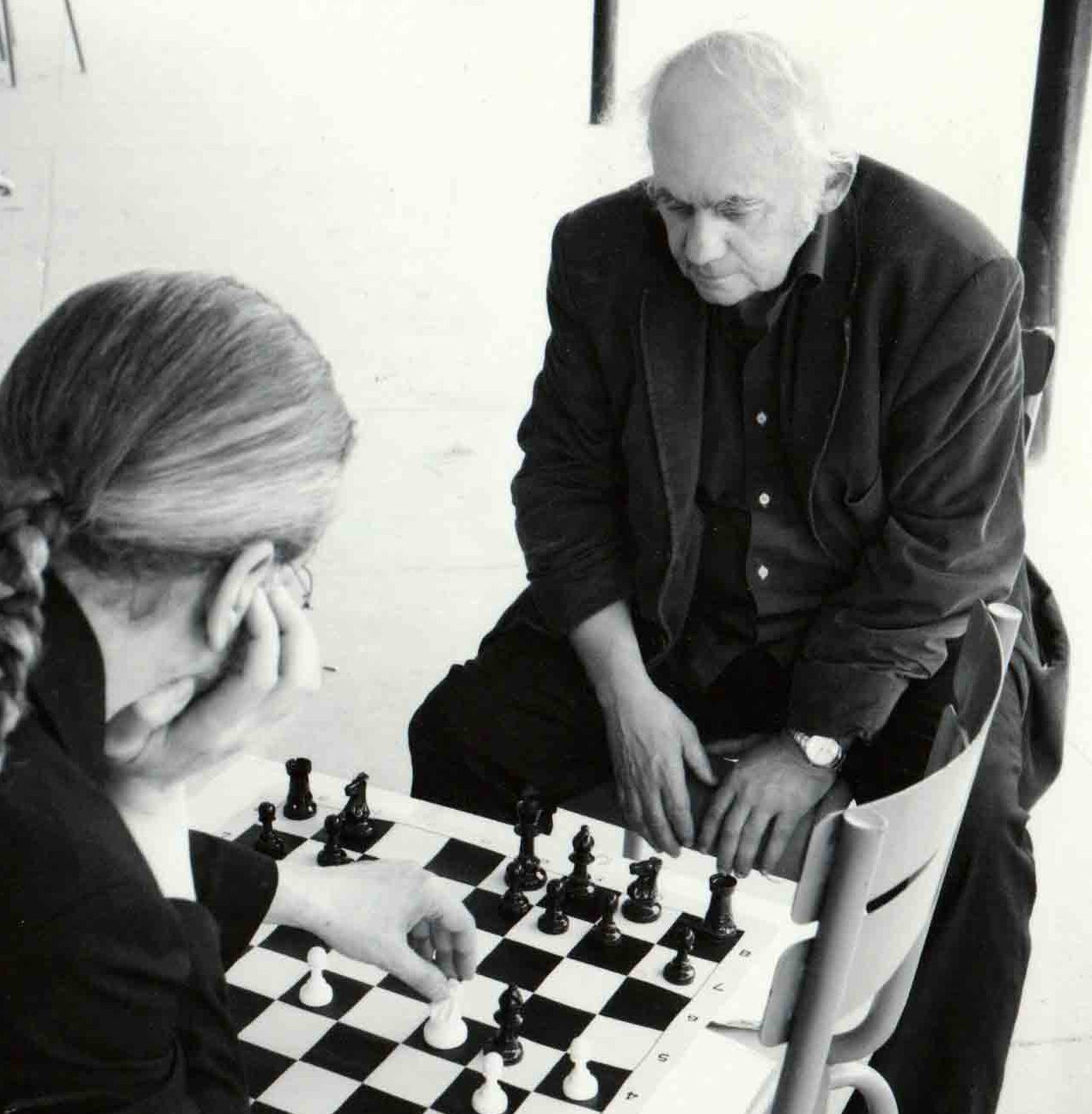

For his second stay in New York, he carries with him letters of introduction to Marcel Duchamp, that eventually proves to be unnecessary: during an initial phone call, just before hanging up, Milshtein suggests a game of chess. A date is set. Duchamp is impressed by the brilliant chess player, formed in the Russian School, and takes him to visit the most exclusive New York chess clubs without ever mentioning a word about painting.

1967

THE SOLANGE FILE is Milshtein’s first literary work. It is the first manifestation, by means of the written word, of his need to confront Life and its absurdities

“I love anecdotes, I love to laugh.

Sometimes, a laugh insinuates itself into my painting. Not that I am sure I like that, but we can’t exist without humor. Even the most tragic things can be overcome by humor. In Central-European Jewish culture, humor plays an enormous role. And then there is a language that today is dead, Yiddish, a humoristic language where each sentence gives rise to laughter, a language that is an escape from the harshness of Life”.

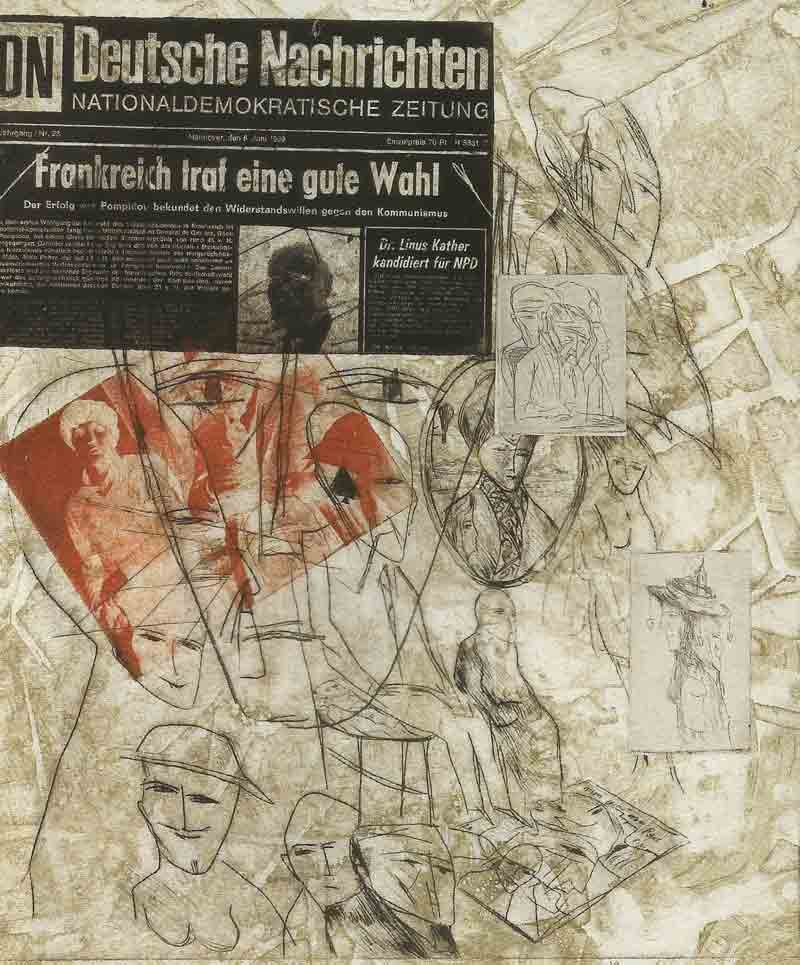

1968

Haim Gamzu succeeds Eugene Kolb as the head of the Tel Aviv Museum of Art. He knows Milshtein from the time when they were both active participants in the cultural life of the Israeli avant-garde. He edits the exhibition catalogue himself.

Like the SOLANGE FILE, the LOUISE FILE appears in the form of a binder bringing together all the elements of a police enquiry. It appears on the 30th of September.

1969

Oddly, for this precocious artist for whom many things seem to come so easily, he enters into a period of withdrawal that will last almost a decade. He steps back from life around him and from his family. His social life withers and painting no longer takes up most of his time. He prefers to play chess and commune with paper, losing himself in the game that is printmaking. He creates a stunning collection of works that fit into a wallet or unfurl in long panels.

1970

Milshtein signals his propensity to move from miniature formats to oversized ones after being invited to stay and work in Geneva with the renown Swedish collector, Theodor Ahrenberg.

“Meeting Teto Ahrenberg was very important: he spoke of painting like an artist and lived for it completely”.

In this city, of which he is particularly fond, because, surrounded by snow, he feels safe and he is able to throw himself into his work at the International Center for Contemporary Printmaking, where he seizes the possibility of experimenting in very large formats.

“For me, going to Switzerland is always a joy.

I return to the country of Madame Martin, my Swiss governess, and to my childhood memories of Kichinev that through her became a virtual Swiss canton”.

Passing through Switzerland, Pierre Gaudibert, the director of ARC (Animation – Research –Confrontation) at the Paris Museum of Modern Art, discovers these large works and decides on the spot to exhibit them.

“At ARC, I exhibited some very large prints created on the presses of the Center of Contemporary Art in Geneva”.

The relationship with Gaudibert and his companion Marie-Odile Briot, who worked at the Museum of Modern Art, develops into a strong friendship.

“I was considered an expressionist, I don’t know why. Similarly, I don’t know if I am representative of Jewish painting as at the same time I have Christian iconography in my blood: I love it when it suddenly appears in an unexpected and surprising manner”.

1972

Milshtein develops a new passion and becomes an ardent bibliophile.

Jean Hugues publishes ALBUM DE TIMBRES (STAMP ALBUM) at Point Cardinal, and would always have prints and works of Milshtein’s in his portfolios. The same year, one of Geneva’s most famous publishers, Rousseau, publishes INTERDITS (PROHIBITED), a series of prints and caustic short texts exploring the concept of total freedom.

He creates JEUX DE CARTES No. 1 with 26 dry points, published by M. Adler and JEUX DE CARTES No. 2, published by the Circle Gallery, New York.

“J’écrivais le plus souvent les textes. Le mot pour moi a une valeur picturale. Encore aujourd’hui, j’ai la passion du livre. Je fais moi-même le papier. J’aime cela. J’ai beaucoup aimé apprendre les techniques liées au livre. Le papier est un des plus beaux supports qui soit pour la peinture comme pour la gravure…

Le livre, c’est mon art conceptuel.

Le vide du livre, le papier, ses fibres, les anciens papiers de Chine, aux fibres qui vont dans tous les sens, tout cela est passionnant. Devant cela, je suis comme un collectionneur passionné. Je peux exprimer tous mes fantasmes. C’est la totalité du livre qui m’a enchanté. Souvent je mentionne un tirage à 50 exemplaires et souvent il n’y en a eu que dix ! Pourquoi ? Je faisais tout moi-même. Je ne pouvais pas déléguer. Par une sorte de jalousie, je ne pouvais pas laisser quelqu’un toucher mon travail. Pour moi un livre n’est pas un objet. Je n’ai jamais aimé les livres objets. Le livre objet est une conception qui n’est pas la mienne. Un livre, c’est un texte, des dessins, des gravures !

Le livre que j’aime le plus est celui que je n’ai pas encore fait.”

1973

Milshtein is shown for the first time in Moscow at the Pushkin Museum.

He publishes The GOBBI, from TIC AU TAC and prepares HOTEL for C. Czwiklitzer of Baden-Baden, a large album on painted paper.

“It was a German publisher, Czwiklitzer, who saw my work in a Russian light. He felt I belonged to the artistic tradition of Russia; it is true that Russian is my mother tongue and many of my themes, just like many of my friends, come from my Russian background. He opened the door to European galleries for my work”.

1974

Milshtein is the subject of a monograph by Jean Adhemar (Director of the National Library of France), Roger Caillois and Michel Waldberg, published by Jacques Goldschmidt, in the collection MUSÉE DE POCHE, as well as RECUEIL DE 50 GRAVURES MINIATURES (Collection of 50 miniature etchings) published by Georges Visat. LES SOUS, one of his most unusual works is presented at the gallery 19 rue de Seine.

1975

During a stay with his friend Ahrenberg, Milshtein meets René Berger, director of the Cantonal Museum of Lausanne, who is seduced by his etchings and proposes a large exhibition.

Having been to Denmark for an exhibition in Odense in 1974, he returns to this country that he very much admires in 1975.

“Denmark is the perfume of cold, of snow, an atmosphere that reminds me of Russia. AND with freedom and tolerance as well!

Publication of FERRY BOAT with the collaboration of Jacques Bellefroid.

1976

A year of intense creative activity associated with paper, etching and his love of books.

Milshtein publishes three works: LE CORNET A DES ADDES (The title being a play of words on ‘The Dice Cup’) with the text of Max Jacob, UNE SEMAINE CHEZ TANTE ROSE (A Week with Aunt Rose) et VODKA + VODKA, a short, but heartfelt, first anthem dedicated to his favorite beverage, to confront the great cold in Denmark, in which he spends several months.

“The Danish imagination and Scandinavian mythology are not without links to Russia, at least the Russia of my memories. I have often exhibited in Odense, Andersen’s birthplace, and I see Denmark as being a country of fairy tales…”

1978

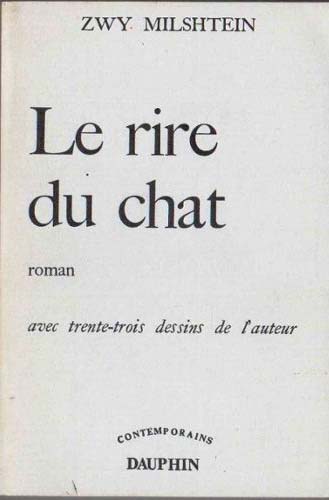

To the painter and the rated chess player, one must add Milshtein the writer. Apart from the stories published in his numerous books, he has also written several plays and in 1978 publishes LE RIRE DU CHAT (The Laugh of the Cat) at Editions du Dauphin, a novel – epistolary, as is often the case with him –the literary and plastic get mixed up, as in this book, where the hero’s portfolio of drawings is inserted in the work.

“Here my drawings don’t illustrate the text, it is the text that depends on the drawings, as they come out of one of the characters’ portfolio of drawings…”

1979

The exhibition MINIATURES at the Negru Gallery is a new opportunity for Milshtein to throw himself, without restraint, into the most surprising, new forms of experimentation.

“I’ve always loved miniatures. The formats that I care for the most: the huge and the tiny. I have even drawn under a microscope –that was an amazing experience… Under the microscope, paper looks like a lunar landscape, with craters and holes, I used my thinnest of brushes but it looked more like a broom and my hand, that I considered very stable, was like a seismograph. I had the greatest difficulty just to execute a simple drawing. Prior to that I had also done portraits on a grain of rice. It comes out of my attraction to extremes: my thoughts always swing from one extreme to another”.

The peerless François Mathey, director of the Museum of Decorative Arts in Paris, invites Milshtein to participate in a group exhibition. The two of them are to enjoy a long friendship based on their insatiable love of painting.

After LE TANGO DE L’HOMME MAL RASÉ (Tango of the Badly Shaven Man), Milshtein follows on with L’ENVOL (The Flight).

1980

Lidis, the publishing house, commissions Milshtein to illustrate Four of Edgar Allan Poe’s Tales of Mystery.

Milshtein spends a period of time in Israel where he meets up again with Nathan Zach who edits Milshtein’s exhibition catalogue at the Rosenfeld Gallery.

Milshtein gives printmaking and painting classes in an atelier of the City of Paris (rue Moliere).

1981

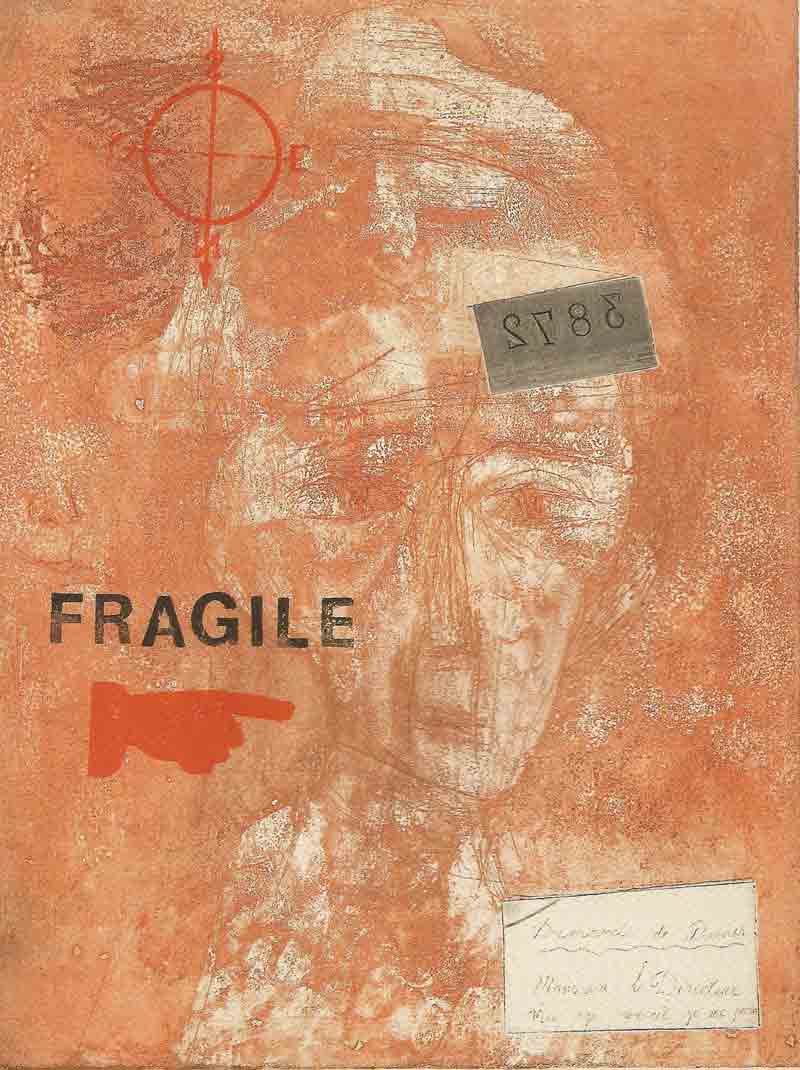

Two literary works HADES and NARCISSUS brilliantly illustrate a new way of using photographic film as a medium by scoring it as a plate for offset printing on Puymoyen’s Moulin du Verger paper made by his friend Jacques Bréjoux. In their own way, they make up the incunabulists of the new incunabulum.

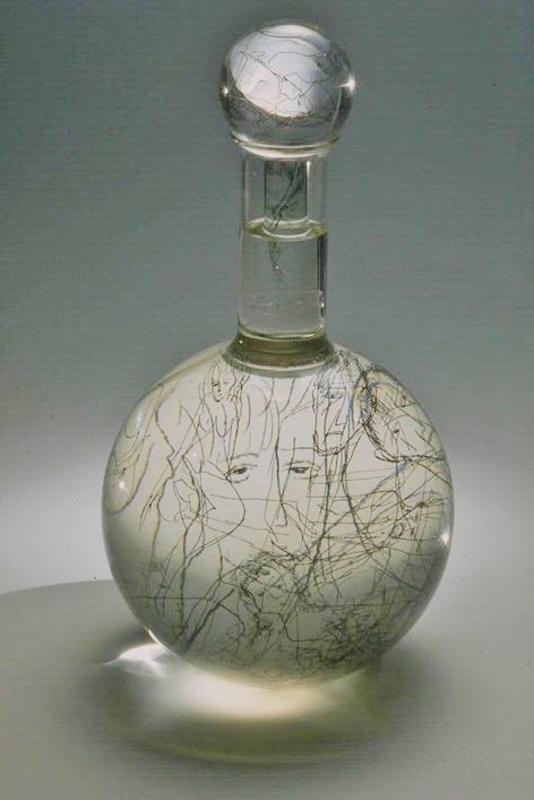

It is in this process that Milshtein realizes that the photosensitive film he is using has the same density as the liquid in which he is submerging it. The optical effect appears to make the film disappear and only the engraved image exists, as though floating.

For the pleasure of his friends, he creates BOUTEILLES (Bottles), one of which the Museum of Decorative Arts acquires, where it is on show in its glass collection.

1982

When Milshtein and Alin Avila meet, Avila organizes the exhibitions at the Maison des Arts in Créteil and at the Avignon Festival. Already a prolific publisher, he shares Milshtein’s love of books. He is enchanted by the artist’s experimentation with materials, but his admiration for the printmaker does not prevent him from giving equal consideration to Milshtein’s painting. An overview of the oeuvre will focus Avila on one thought: to bring Milshtein back to painting, the art he should never have neglected.

Publication of DOUX SOUVENIR

1983

Alin Avila organizes Milshtein’s first major retrospective.

1984

Milshtein contributes a painting and six large lithographs to the exhibition “The KAFKA Centenary” at the Pompidou Center and ON INVITATION at the Museum of Decorative Arts in Paris.

Chen Yen Fon, Taiwanese art critic and collector organizes a presentation of Millstein’s work in Taipei and Taichung and publishes a comprehensive study of his work.

1985

Alin Avila becomes Milshtein’s agent and sets about having the principal works, that had been presented in Créteil, exhibited in major cultural centers and the Maison de la Culture, as well as abroad.

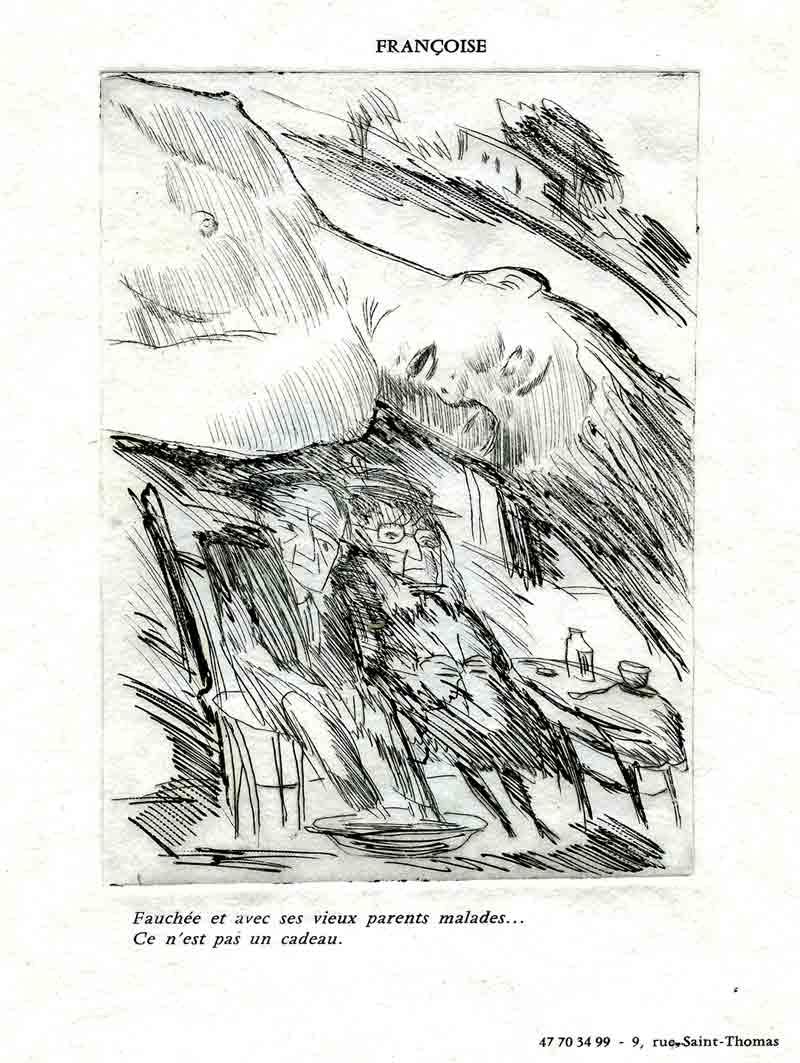

PAPILLONS NOCTURNES DE PARIS (Nocturnal Butterflies of Paris) is a collection of texts and etchings in which the anthropomorphic butterflies illustrate cautionary tales.

1986

A third exhibition in Odense is set up in an old, abandoned factory. This occasion presents Milshtein with the opportunity to swing from one extreme to the other of his passion. After a period dominated by small formats, he sees things on a large, even gigantic, scale!

“At last I could create some huge gouaches – that’s what I call them, but in fact they are water-based acrylics on large rolls of paper: seven by two and ten by two meters!”

He meets Arris Karamounas owner of a very large gallery in Geneva, who exhibit his work on several occasions.

He publishes LE CARNET D’ADRESSES DE BARBE DE BLEUE JUNIOR (Bluebeard Junior’s Address Book) with the Mustad Gallery in Gothenburg.

1987

Milshtein sets up his studio in the rue Hélène, in the 17th arrondissement of Paris, in a studio so large that he can paint with a broom on mega sized paper. In his other studio, situated in his apartment in the rue Molière, near the Palais Royal, he creates his small format works, but not without a cost to the sinks and bathtub in which he mixes up his own paper, based on a recipe from a paper maker in Angoulême, a true poet of papermaking, who shared his techniques and with whom there was a shared passion

1988

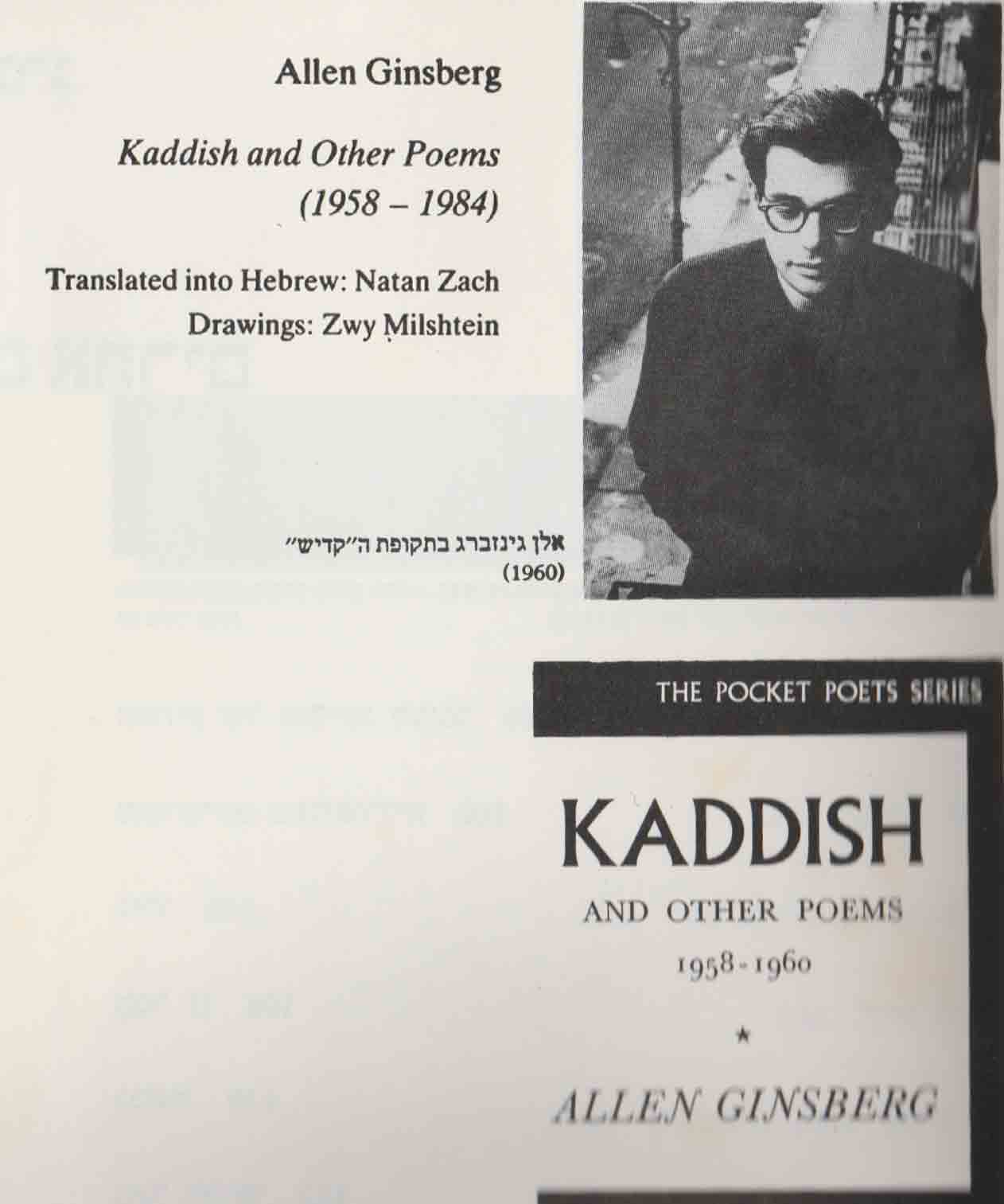

Exhibition of Milshtein on the occasion of the Hebrew translation of Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish; Milshtein illustrates KADDISH AND OTHER POEMS that was to become a cult book of the Beat Generation.

“It was Nathan Zach who introduced me to Allen Ginsberg. Nathan Zach is one of the foremost Israeli poets and has been a friend forever. I used to hang out with him when I was a young art student and I always visit him when I go to Israel. He is part of the left-wing movement, one of the Peace Now activists”.

1989

With renewed vigor, Millstein undertakes a fresh series of prints. Always keenly inventive, he creates plates for eau forte printing on engraved zinc from reworked film.

Caroline Benzaria publishes ZWY MILSHTEIN ÉCRITS ET ACIDE (Zwy Milshtein Writings and Acid) entirely devoted to the books and writings of Milshtein.

LE DIVAN D’YVAN (Ivan’s Divan) is published by BLM.

1990

Alin Avila recognizes in certain aspects of Milshtein’s work, particularly in QUO VADIS, a synthesizing of religious themes and the Shoa, at the same time bringing in Catholic symbols – as well as pornography.

“It is true that when I was with Katia Granoff, I often showed works that were to be milestones in my career. In the series DIX COMMANDEMENTS, TON PERE ET TA MERE TU HONORERAS (the Ten Commandments, You Will Honor Your Father and Mother) was a very important work; of course more influenced by religious painting than by Christian doctrine… Before that I had exhibited LES CANNIBALES (LE REPAS DES FAUVES), (The Cannibals, Supper of the Beasts), where there is a yellow clown hanging on a sort of gallows nailed into the frame. QUO VADIS, that I worked on for almost two years, was the sole work on show at my last exhibition at her gallery…”

To account for his attraction to Christian subject matter, Milshtein reflects back on his first contact with the great tradition of religious art in Russia and to its importance to the Russian people in the times of great suffering and misery during the war.

“It goes back to around 1943 or 44, in Georgia, the moment when they reopened the churches that had been shut for so long, offering a sort of entertainment for those who didn’t go to pray. I discovered painted icons: for me, it was mind blowing…”

1991

Milshtein participates in the publication LE FOU PARLE (The Madman Speaks) with his friends Lise Lecoeur, Michel Parré, Denis Poupeville and, of course, Jacques Vallet.

Roland Topor invites him to participate in the final exhibitions of the Groupe Panique

“Topor c’est pour moi un rire. Ensemble, on déambulait dans les bistrots, on riait… C’est lui qui m’a invité aux dernières expositions Panique…”

1993

As a bet, Milshtein presents a series of works at Area with no figures, heads or faces.

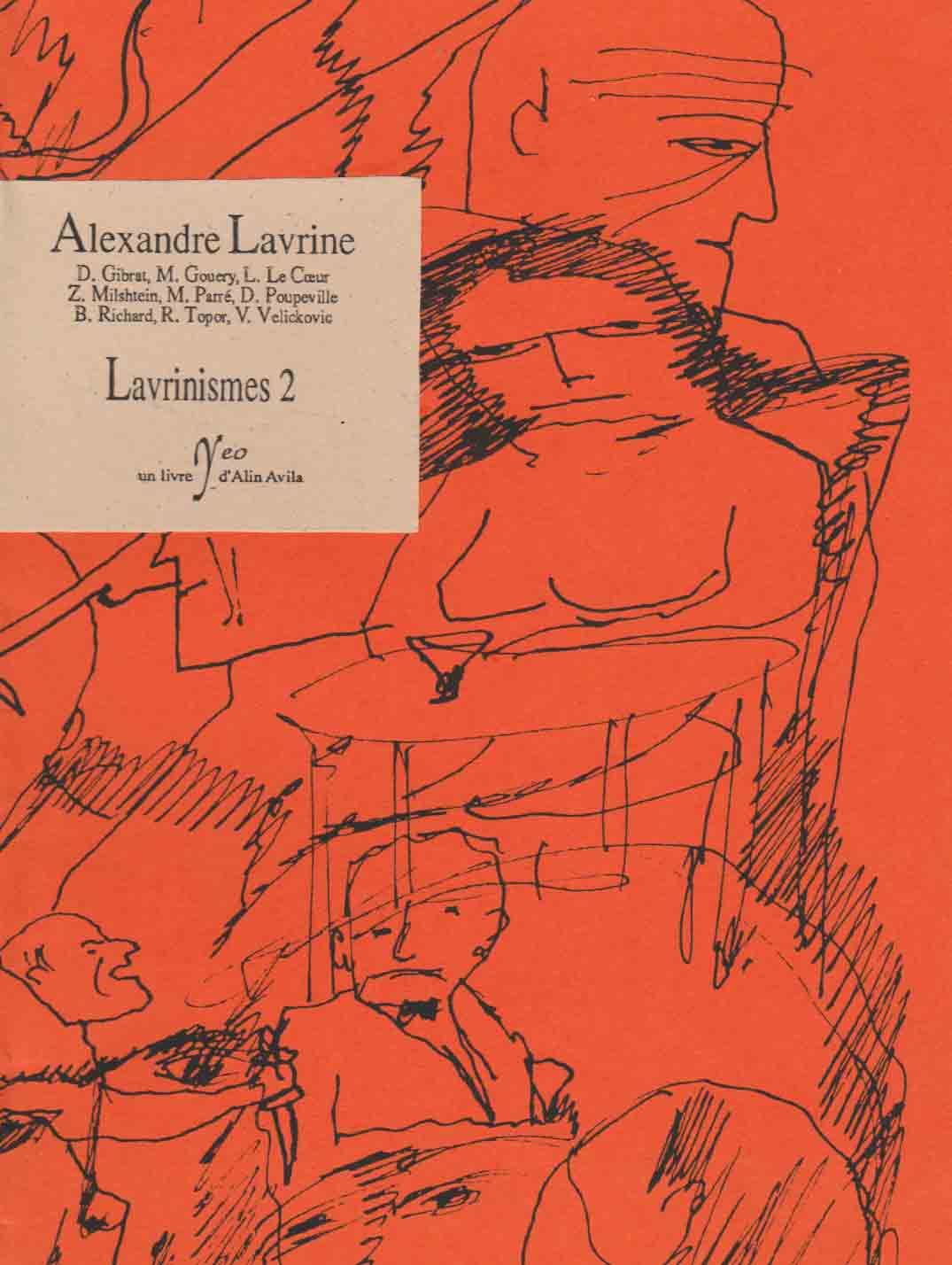

Return to Moscow where his friend Lavrine, a talented publicist, proposes a retrospective in the Maison de la Presse. Milshtein publishes LAVRINISME 1 À LIRE DANS L’ASCENSEUR (Lavrinism 1 To Be Read in the Elevator) and Area LAVRINISME 2 (illustrated by Milshtein et D. Gibrat, M. Parré, D. Poupeville, B. Richard, R. Topor, V. Velickovic).

30 works on paper enter the collection of the Museum of Toulon and are presented in the exhibition Eulogie to Painting.

“I felt saturated by faces. I thought to myself that a collection of objects would have the same effect and at the same time a renewal… I spent years in overcrowded trains during the war, where people were squeezed in like animals. When my mother and brother would alight in search of food, I scrutinized the faces around me in the hope of finding a familiar one, of someone who would look after me. I would experience a similar sensation in the Paris metro, where I would find myself in a world reminiscent of the refugee trains during the war”.

1994

“There is an indifference when I paint, my hand controls everything. One could believe that there was no brain. And I am quite happy not to have a brain when I paint. My hand does everything. I am quite happy that the brain does not interfere with my work. It destroys all artistic impulse. One wants to express certain things, but if one starts to think about them, one can no longer express them. Critical evaluation steps in. The hand can’t be left unrestrained in daily life or there would be nothing but blows and wounds. But in painting, leaving the hand to express itself is the most natural of things to do..

One reaches a paradox: but the great problem that humans face is to manage and recognize contradictions. The indifferent hand says essential things, it is like that, acts by instinct, on reflex. The hand reacts automatically and things come out of it, of a deeper nature, without being filtered through a conscious process. Painting, and art in general, is savagery and violence, all that I cannot do as a human being living in a society. I don’t want to be responsible for the images that my hand draws, but these images are mine only… I think about a painting that I want to do only outside the act of painting. When I paint, I do not think. There have been instances that I just sit like an idiot, mouth open, eyes staring. And if my wife asks me what I am doing, I reply that I am painting. I draw from within – but from where? Something that my hand will search for, and that will then belong to it alone”..

1995

A retrospective in two parts is organized at the Museum of Modern Art in Troyes, as well as in the Palais Benedictine in Fécamp, France, with more than a hundred works exhibited, showcasing a half century of work.

1996

Poland honors Milshtein with a series of five exhibitions in its major cities, including the Królikarnia Museum in Warsaw. The Poles appreciate Milshtein’s quirky take on Life and have LE RIRE DU CHAT and LE CHANT DU CHIEN (The Cat’s Laugh and The Dog’s Song) translated into Polish.

1997

With ET DIEU INVENTA LA VODKA (And God invented Vodka) Milshtein creates seven short poems accompanied by seven paintings of seven meters in size that illustrate Milshtein’s version of Creation.

He subsequently produces an album of prints based on these poems.

“In the end it comes back to my attachment to vodka. I wanted to celebrate vodka on several levels. In the end, who am I?

I wanted to come to an understanding with the East, symbolized by vodka. In addition, vodka cured me of tachycardia, for which no medication had any effect. LES SEPT VERRES (The Seven Glasses) is my tribute to this beverage…”

1999

Combining his love of mind games and painting, Milshtein dedicates himself to a series in homage to Gainsborough for an exhibition in London.

2000

Milshtein exhibits at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sopot, the Deauville of Poland, thanks to Joanna Wilhelmi.

After his exhibition in Poland, Milshtein sets off to conquer the East:

He exhibits in Ukraine, at the Museum of Russian Art in Kiev, thanks to Anne-Marie and Roland Pallade.

A national tribute is organized in Moldova and an exhibition is dedicated to him organized by Georges Diener in Kichinev.

Accompanied by Elisabeth Hoffman, his partner, they visit Kichinev, where he finds his old home after a period of sixty years, but not without difficulty as all the street names had changed.

During the year, Christiane Botbol sets up an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in Cluj, Romania.

A retrospective is held in Cergy Pontoise and PETITES CONFIDENCES and le CHANT DU CHIEN are published.

Exhibition “Nattier and me” in Paris, Nattier was dubbed “the Ambassador of French Elegance” and Milshtein pays him homage.

2001

Yves Koby organizes an exhibition in Vienna incorporating some of Milshtein’s biggest canvases.

2002

From 1986, Milshtein takes a lively interest in computer graphics. With support from Epson, he refines a technique of digital reproduction that allows him to produce color prints, of an astonishing quality, of which he publishes a reduced run. He becomes a “sage” at Epson, which opens a new door to the creation of his artistic books.

Following an initiative of the French Senate, Milshtein exhibits for the first time “l’homme au parapluie” (Man with an Umbrella) in the Luxemburg Gardens’ exhibition “Art or Nature”.

As a result of the success of the Sopot exhibition, Joanna Wilhelmi organizes a new exhibition in Olsztyn, Poland.

2004

In the framework of the event “The Peregrine Artists”, Milshtein invites Shelomo SELINGER to participate in the exhibition “Journey Around A Chess Board”, organized by Art Sénat, a cultural initiative of the French Senate, and exhibits “Le Château de Cartes” (The Card Castle).

His digital works “Journey Around A Chess Board” are exhibited amongst assiduous chess players in the Luxemburg Gardens: 18 posters of chessboards, each incorporating a text of the players’ hilarious thoughts. The posters are subsequently included in “Journey Around a Chess Board”, Milshtein’s first digitally created book.

“Chess is like vodka, it doesn’t relinquish its grip on a Slav artist just like that. It’s a bit like a relapse”.

Publication of “Journey Around a Chessboard” (édition recherche).

2005

With the collusion of two collectors, Christiane and Peter Zimmerman, Milshtein discovers the area of Beaujolais. After numerous visits with them, Milshtein sets up a large studio in an ancient flourmill. He and Elisabeth divide their time between Clamart and Gleizé.

2006

Several exhibitions take place, notably in the cellars of Chateau l’Angélus in Saint-Emilion, organized for Claude Péruzat and those for the “BOITES À SECRETS” (Trick Boxes with Secret Compartments) at the Area Reserve, as well as at the Gallery L’Oeil Ecoute in Lyon by Anne-Marie Pallade. Large formats are prepared for the Ghent Market in Belgium.

Directed by Valéry Dekowski, LE CHANT DU CHIEN (The Song of the Dog) is staged by a troupe of thirteen actors at the Rachi Center (Paris). The play, revisiting the legend of Faust, takes place between Paris, Poland and Venice and carries a whiff of herrings and vodka. It is the beginning of an important artistic collaboration between the AMAVADA troupe and Milshtein.

Exhibition “Le Parti du Niet-Niet (le Dada au negatif”) exhibition of humoristic computerized graphics gives rise to the second book produced by computerization.

2007

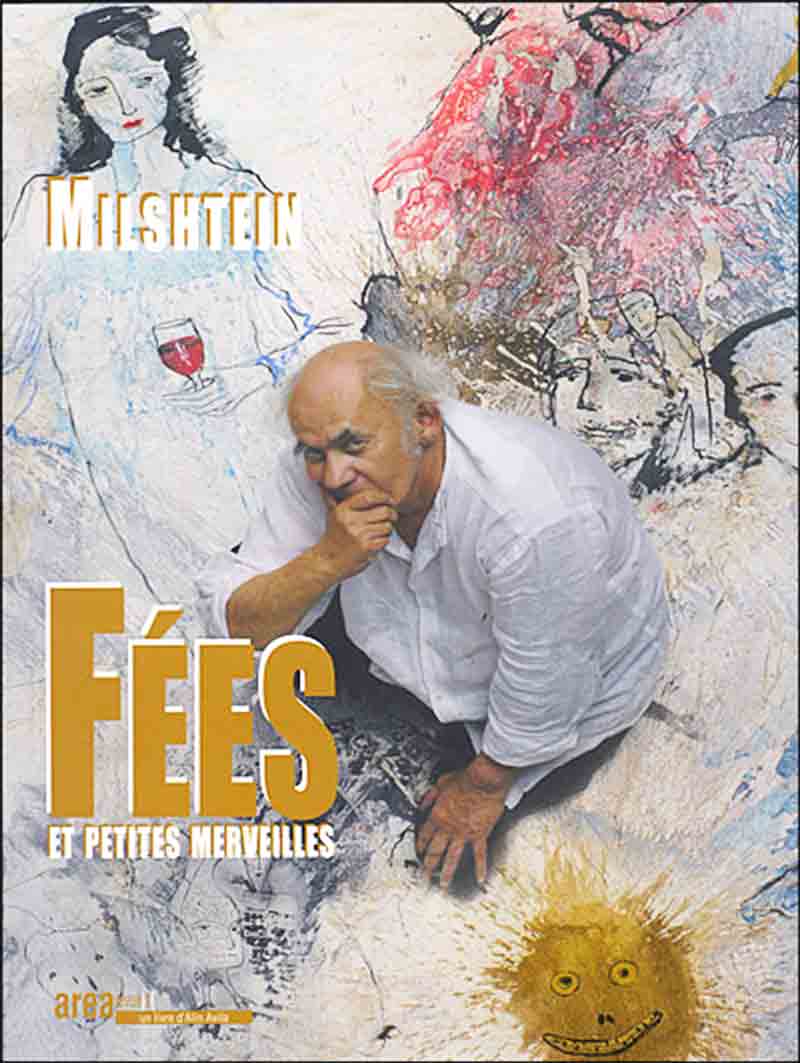

Invited by the Senate, Yves Marek and Alin Avila, for a summer exhibition in the Luxemburg Gardens’ Orangerie, Milshtein produces “Fées et Petites Merveilles” (Fairies and little Marvels), joyful and amusing canvases that evoke fairies and imps, dragons and even magic brooms. Enormous canvases hang freely from the ceiling, like portals between our world and the world of marvels.

An exhibition follows in the Espace Berggruen, rue de l’Université in Paris, (with the support of Serge Cachan and Alin Avila). This exhibition enjoys an enormous success and gives rise to the publication of the book “Fées et Petites Merveilles” published by Area.

During the year, Fréderic Biessy, the theatrical impresario, acquires a painting of Milshtein’s but finds it is unsigned; Milshtein goes to his home to rectify the oversight, which marks the beginning of a friendship that leads to future surprises in the theatre.

2008

During the summer, Milshtein exhibits “Les muses s’amusent” (The Muses Amuse Themselves) at the Boucher-de-Perthes Museum in Abbeville. With a lot of fun and in his own style, Milshtein takes a stroll through the history of Art, creating, with derisive humor, about thirty canvases.

The Boucher-de-Perthes Museum acquires “Remède Miracle” (Miracle Remedy), Christ painted in acrylic on wood and inspired by the Issenheim Alterpiece, that was also inspiration for Picasso.

Caen’s Almavada troupe accompany Milshtein to Chisinau in Moldova and to the theatre festival in Sibiu, Romania.

Milshtein returns to Chisinau for the second time and is confronted with the astonishing sight of a transformed city living a western lifestyle.

2009

Aldo and Nathalie Peaucelle introduce Milshtein to Patrice Charavel, the director of the Musée des Moulages in Lyon. Patrice Charavel feels an immediate liking for Milshtein. From this encounter springs the exhibition “Du bois grave à la digigraphie, Restrospective” an exhibition of prints set amongst masterpieces of ancient Greek and Roman sculptures.

“I was next to the Venus de Milo and was relieved that she didn’t slap me for having got a bit too close”

Publication of the exhibition catalogue “Du bois grave à la digigraphie, Restrospective”.

The Chybulski Gallery (Ville sur Jarnioux) organizes an exhibition with works by Manray, Arman, Hartung and Milshtein.

2010

Major exhibition in numerous locations in Reims, including the sumptuous Palace of Tau, “VENTS D’EST VENT D’OUEST: (East Wind West Wind) organized by the Recto-Verso Association and Marie Christine Bourven (former printmaking student of Milshtein’s).

“There is a large hall in the Palace chapel in which I exhibited my drawings and where, in a moving tribute, I was able to present a portrait of my brother who had just recently died a violent death”.

Large format drawings are exhibited in the greenhouse of Saint Etienne by Avila.

Frédéric Biessy introduces Milshtein’s work to Claudia Stavisky (theatre director and Director of the Théatre des Celestins in Lyon). She commissions him to create 20 posters for the plays produced during the Year of Theatre events.

During the 8th International Printmaking Triennial in Chamalières, organized by the Contemporary Art Movement of Chamalières, Milshtein is the guest of honor and given a prize.

2011

Milshtein designs the program cover for the Gleizé Theater on the proposal of Madame Elisabeth Lamure, Senator and Mayor. She was very supportive of Milshtein.

2012

Roland and Anne Marie Pallade open a gallery in Lyon and renew contact with Milshtein in May with “Acte II Scène III”.

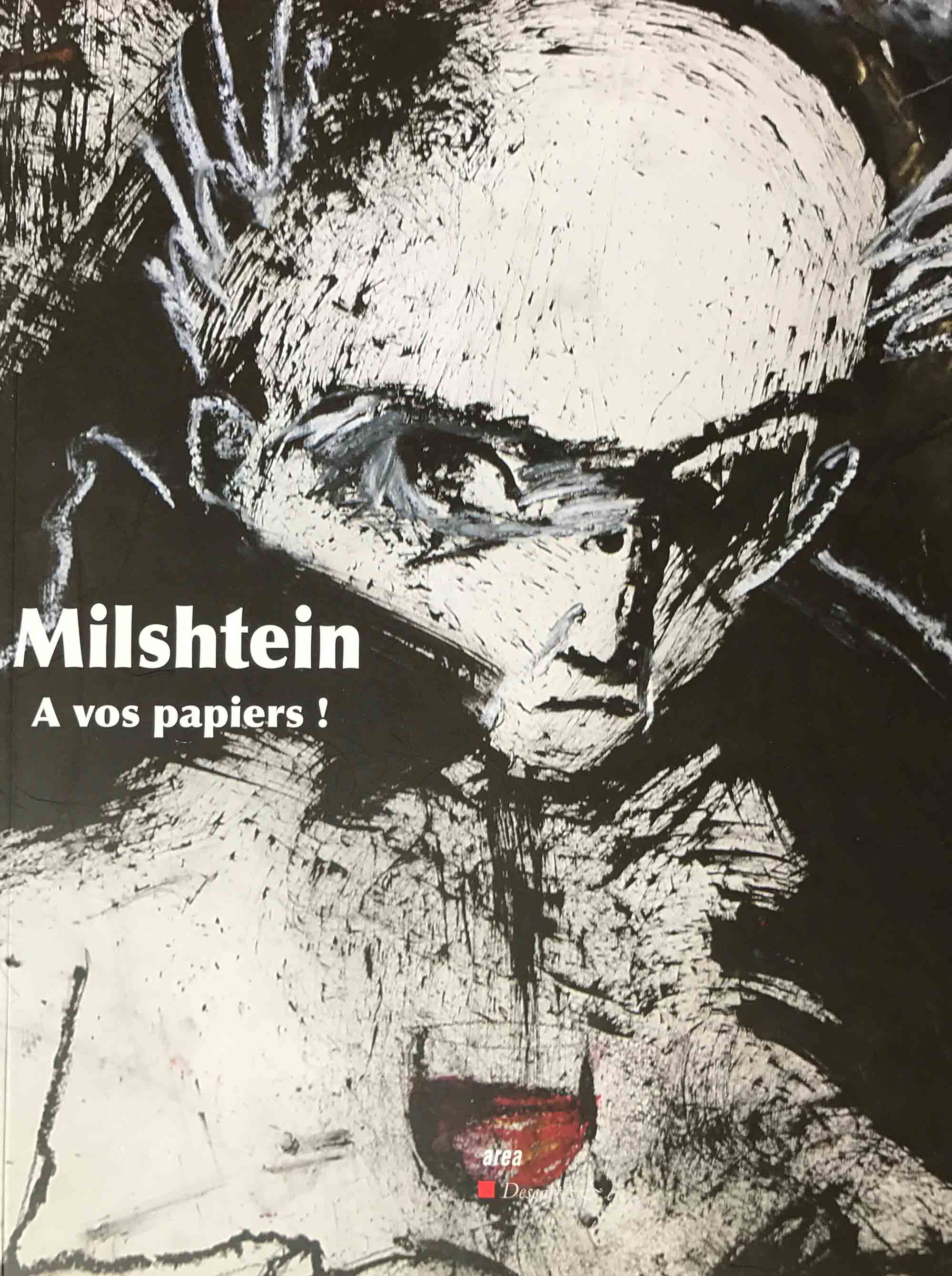

The Museum of Sens decides to mount a retrospective of Milshtein’s work in paper, a medium for which he has particular affinity.

“À vos papiers !” is combined-published by the Museum of Sens and Area 2012.

“Le poète Rimbaud” is exhibited for the first time at Tobbogan (Decines) “« le Géant pour Plaire, la Miniature pour me Cacher ». Creation of a huge curtain commissioned for an installation in a private church belonging to Dominique Guiho, the renowned collector (a dilapidated and deconsecrated church from the 1950’s destined to become a place for cultural creation in Guingamp “the Drunken Chapel”, so named with a nod to Rimbaud’s “Drunken Boat”).

His play, « Brèves de bar à Vodka du Cabaret Milshtein », is performed at the Toboggan (Le Chant du Chien – troupe Amavada)

2013

Milshtein participates in the event CHIFRA (China-France) during the FIAC OFF on the Champs- Élysées. Milshtein and Alin Avila’s paths separate after 31 years of collaboration.

The book of prints “LES GRENOUILLES D’ARITOPHANE” (ARISTOPHENES’ FROGS) is published by Chybulski who also organizes a double exhibition with works by Kokoschka.

2014

After several complicated approaches, Milshtein creates his second stage curtain, for the Theater of the Celestines, in Lyon. Mr. Roland Tchénio, MD of Group Toupargel and a patron of the arts, donates the curtain to the theatre.

In the fabrication, Milshtein goes to the manufacturer Gerriets, where they make up the giant curtain and he is very taken by this enormous, but magical space, a place filled with people who are passionate about sets and fabrics for the stage…

In the beginning of the 80s, Milshtein and Christine Virmaux (restorer and gallery owner) meet, when they are both working for the Granoff Gallery. A great friendship, enduring more than 30 years, finally brings them together again with a beautiful exhibition of miniatures at the Patriarchs Gallery.

“When I was small, sorry, I mean when I was young, as ‘small’ I still am, I collected stamps and I was fascinated by their size and their beauty.

There was one called ‘Ten Years Without Lenin’, a very rare stamp. Naturally, I wanted to copy it to show off in front of my classmates at school. It was worth at least ten bottles of vodka. Therefore I started to copy it and in so doing, I began to admire and to love the miniature format, which had a magical power, like vodka – the miraculous medicine for all of humanities’ ills.

Imagine all our great leaders shut up in a matchbox, rather like a tiny gulag, that can be thrown away in the bin, as in my mind, as a child, it was their fault that the October Revolution failed”.

2015

A year after the Celestins curtain, the patron Roland Tchénio funded the decoration of the liberal synagogue “Keren Or” in Villeurbanne. Milshtein creates a fresco (with texts taken from the Talmud with the graceful caligraphy of Rachi’s writing), stained glass windows and a clock (inspired by the Hebrew Clock in Prague).

When representatives of the organization “Vivante Ardèche” visit Milshtein and his companion, Elisabeth, in his atelier in Gleizé they discover a multitude of means of expression used by Milshtein, as well as the use of the most unexpected of materials.

Impressed, Mr. Place and the association “Vivante Ardèche” organize an exhibition in the Chateau de Vogüé, a magnificent stone showcase suspended in a sublime setting above the river.

“Château sans Espagne où l’espoir vient par le regard” (Charavel) (Castle without Spain or Hope comes through the Eye) – Charavel

2016

Major European Heritage Days exhibition in Metz celebrating Jewish-Lorraine culture, set up in different locations across town: the Cloister of the Récollets, the New Temple and at the Germans’ Gate.

“The director of Museums in Metz was going backwards and forwards between Metz and Gleizé in a hired van to transport my paintings. It is amazing what he did, as a museum director: it was truly an act of heroism in the sphere of painting”

Chybulski organizes two further exhibitions: one in Germany, at the Hinter dem Rathaus Gallery and one in Italy at the Utopia in Rome.

The list of some professional bullshit. The big ones, I keep them for myself and my analyst.

1934 – As my late friend Henri Salvat said, it is better not to be born, but it happens so rarely.

1943 – Tried to make oil paint with petroleum jelly and pigments. As the paint did not dry, I had to throw my masterpiece.

1948 – Changed name from Grisha to Zwy.

1954 – Did not take trade courses.

1956 – Worked on raw plastic without instructions. The result was smashing, an explosion that spared me by a miracle.

1961 – Engaged myself in a reckless manner into painting under a microscope for an invisible result, or in spending hours on a grain of rice that I would lose immediately.

1968 – Made paintings too big that cluttered the workshop.

1970 – Did not know how to hold my tongue in public, especially in front of officials.

1981 – Always kept losing my glasses.

1999 – Bought a hunter’s vest with too many pockets; like that one can be sure not to know where things are.